If you went to college in the States, you are sure to shudder at the memory of analogies. Analogies are the word pair bane of your existence that, until 2005, dominated the verbal section of the SAT – the entrance exam required by most colleges in the country. For some reason, the exam writers believed that students’ ability to understand the relationship between two words was an effective way of predicting future academic success. The test would provide a word pair, such as “chef : food,” and you needed to review a list of other word pairs and ascertain which of these pairs shared a similar relationship to the given pair. In this case, “carpenter : wood” would do, for example. Chef is to food as carpenter is to wood. Clear as mud, yes?

If you went to college in the States, you are sure to shudder at the memory of analogies. Analogies are the word pair bane of your existence that, until 2005, dominated the verbal section of the SAT – the entrance exam required by most colleges in the country. For some reason, the exam writers believed that students’ ability to understand the relationship between two words was an effective way of predicting future academic success. The test would provide a word pair, such as “chef : food,” and you needed to review a list of other word pairs and ascertain which of these pairs shared a similar relationship to the given pair. In this case, “carpenter : wood” would do, for example. Chef is to food as carpenter is to wood. Clear as mud, yes?

Not surprisingly, I have spent nary a second thinking about analogies since I took the dreaded SAT. That is, until I embarked on a search for a recipe for yemiser w'et, an Ethiopian lentil stew. Every recipe reminded me of Russian nesting dolls because in order to make the main recipe, you first had to make at least two other, smaller recipes. Ergo:

“Russian nesting dolls : Ethiopian lentil stew” as “Recipe : Dish.”

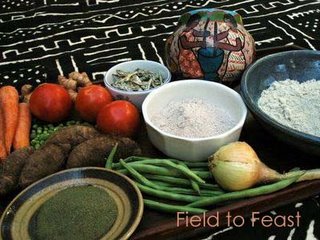

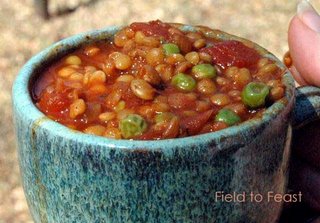

The yemiser w'et recipes I found all required berbere (a spice mixture) and niter kebbeh (spiced ghee). Now, I don’t know about you, but berbere and nitar kebbah aren’t usually on the shelf at my local supermarket. After consulting with Recipe Zaar and Food and Home Entertaining, I combined recipes for these two ingredients with several recipes for the main dish to develop the one consolidated yemiser w'et recipe below. It looks more complicated than it actually is – many of the ingredients are spices that you simply measure and add. Once finished, you’ll have a delicious, spice-infused tomato, lentil and green pea stew. One recipe, one dish. No Russian nesting dolls.

The yemiser w'et recipes I found all required berbere (a spice mixture) and niter kebbeh (spiced ghee). Now, I don’t know about you, but berbere and nitar kebbah aren’t usually on the shelf at my local supermarket. After consulting with Recipe Zaar and Food and Home Entertaining, I combined recipes for these two ingredients with several recipes for the main dish to develop the one consolidated yemiser w'et recipe below. It looks more complicated than it actually is – many of the ingredients are spices that you simply measure and add. Once finished, you’ll have a delicious, spice-infused tomato, lentil and green pea stew. One recipe, one dish. No Russian nesting dolls.

Ethiopian Lentil Stew (Yemiser W'et)

Serves 8

SPICED GHEE

½ cup ghee (use vegetable oil as a substitute)

2 tablespoons chopped onion

1 garlic clove, minced

½ teaspoon fresh ginger, grated

¼ teaspoon turmeric

2 cardamom pods, crushed

1 small cinnamon stick

1/8 teaspoon fenugreek seeds

3 leaves fresh basil

LENTILS

2 cups dried brown lentils, picked over

4½ cups water

BERBERE

3 teaspoons cumin seeds

1 teaspoon ground cardamom

¼ teaspoon whole allspice

1 teaspoon fenugreek seeds

1 teaspoon coriander seeds

8 cloves

1 teaspoon black peppercorns

15 dried red chilies, crushed

¼ teaspoon ground ginger

¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 teaspoon ground turmeric

3 tablespoons plus 1 teaspoon sweet paprika

1 teaspoon salt

STEW

2 cups onions, chopped

4 cloves garlic, minced

4 cups tomatoes, chopped

1 cup tomato paste

2 cups vegetable stock

2 cups fresh green peas (or frozen peas, defrosted)

Salt and pepper, to taste

Put the ghee in a small fry pan over medium heat. Add all the ingredients listed and turn the heat to low. Simmer for 30 minutes.

Put the ghee in a small fry pan over medium heat. Add all the ingredients listed and turn the heat to low. Simmer for 30 minutes.

Meanwhile, rinse the lentils and put them in a pot with the water. Bring to a boil, lower heat to a very gentle simmer, and cook, partially covered, for 25 minutes or until tender. (If the lentils are tender and there is still water remaining in the pot, simply drain.) Set the lentils aside.

Next, prepare the berbere. The spice mixture is very strong, so it is a good idea to open all the windows in the kitchen; otherwise, you may have a coughing and sneezing fit. Put a fry pan over medium-high heat and add all the spices listed (except the salt). Cook for 2 minutes, stirring constantly. Add the salt, and grind all the spices in a spice grinder, or with a mortar and pestle.

At this point, your ghee should be almost ready. Strain the mixture using a cheesecloth and discard the solids. Return the newly-spiced ghee to medium heat in a large saucepan, and begin to make your stew. Add the onions and garlic to the spiced ghee and sauté until the onions are just translucent, about 5 minutes. Add 3 teaspoons of the berbere (saving the rest for the next time you make this dish!) and sauté for a few minutes more, stirring occasionally to prevent burning.

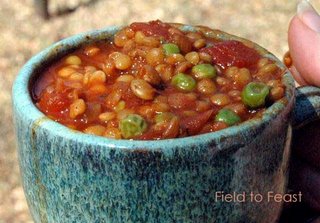

Mix in the chopped tomatoes and tomato paste and simmer for another 8 minutes, stirring occasionally. Add the vegetable stock and the cooked lentils, and continue simmering and stirring for 10 minutes. Add the green peas and cook for an additional 5 minutes. Season with salt and black pepper, and you are finished!

Yemiser w'et is typically served with injera bread – the Ethiopian mealtime staple made with teff, the smallest grain in the world. This bread always reminds me of an undercooked pancake, which is not a good thing. So, as an alternative, I served the lentil stew with some Indian rotis we had on hand. Pita bread or tortillas would also work well. Since the stew is often accompanied with yogurt or cottage cheese, I spread smooth cream cheese on the rotis, and we used them to scoop up the stew.

“Chili : Spicy” as “Yemiser w'et : Yum.”

Tags:

recipe, Ethiopia, lentils, soup, stew, lentil stew, main dish, yemiser w'et, Field to Feast, food blog, Africa

Last Saturday, Mark, Dorothy and I had a memorable visit to Mbare Musika. This Saturday, Dorothy and I began cooking with our market bounty. Today’s lunch? Sadza rauzviyo, served with kapenta relish. Before we get to these recipes, a here’s little background on sadza, kapenta and relish.

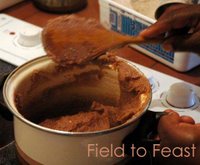

Last Saturday, Mark, Dorothy and I had a memorable visit to Mbare Musika. This Saturday, Dorothy and I began cooking with our market bounty. Today’s lunch? Sadza rauzviyo, served with kapenta relish. Before we get to these recipes, a here’s little background on sadza, kapenta and relish. Bring the water to a boil in a medium saucepan. Turn heat down to medium-high and sprinkle ¾ cup of the meal (a big wooden-spoonful) over the top of the boiling water. Stir briskly, pressing the wooden spoon against the side of the pot to remove any lumps. Keep stirring for about five minutes.

Bring the water to a boil in a medium saucepan. Turn heat down to medium-high and sprinkle ¾ cup of the meal (a big wooden-spoonful) over the top of the boiling water. Stir briskly, pressing the wooden spoon against the side of the pot to remove any lumps. Keep stirring for about five minutes. When the mixture is smooth and is beginning to puff and bubble like lava (or, to my eye, the hot mud pools in Rotorua), stop stirring and keep a safe distance from the pot so you will not get hit by a lava burst. After 10 minutes, add another ½ cup of the meal and stir, stir, stir. Once it has been absorbed, add another ½ cup of meal. Stir, stir, stir. Add the remaining ¼ cup, and stir again. The sadza should be thick and smooth, and your arm will be tired. Spoon the sadza onto a plate and let it cool for a few minutes.

When the mixture is smooth and is beginning to puff and bubble like lava (or, to my eye, the hot mud pools in Rotorua), stop stirring and keep a safe distance from the pot so you will not get hit by a lava burst. After 10 minutes, add another ½ cup of the meal and stir, stir, stir. Once it has been absorbed, add another ½ cup of meal. Stir, stir, stir. Add the remaining ¼ cup, and stir again. The sadza should be thick and smooth, and your arm will be tired. Spoon the sadza onto a plate and let it cool for a few minutes.