This year I read The Orchid Thief. I know, I know, I’m a little behind the pop culture curve – the book was a bestseller in 1999 and the inspiration for Adaptation’s wacky tale in 2002. It follows author Susan Orlean’s real-life foray through Floridian swamplands to understand the intangible mystique of orchids, a mystique that has inspired lifelong hobbies, unhealthy obsessions and even criminal activities. Her descriptions of orchid flowers are evocative and lush. Says Orlean of the ghost orchid, the passion of her protagonist, John Laroche:

This year I read The Orchid Thief. I know, I know, I’m a little behind the pop culture curve – the book was a bestseller in 1999 and the inspiration for Adaptation’s wacky tale in 2002. It follows author Susan Orlean’s real-life foray through Floridian swamplands to understand the intangible mystique of orchids, a mystique that has inspired lifelong hobbies, unhealthy obsessions and even criminal activities. Her descriptions of orchid flowers are evocative and lush. Says Orlean of the ghost orchid, the passion of her protagonist, John Laroche:

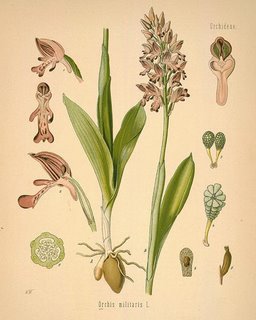

“The flower is a lovely papery white. It has the intricate lip that is characteristic of all orchids, but its lip is especially pronounced and pouty, and each corner tapers into a long fluttery tail. … These tails are so delicate that they tremble in a light breeze. … Because the plant has no foliage and its roots are almost invisible against tree bark, the flower looks magically suspended in midair.”

This stunning flower blooms, briefly, only once a year.

After reading The Orchid Thief, I could certainly understand how the flower’s unparalleled variety and unconventional beauty, combined with the rarity of certain species, collude to keep people enthralled. But when I flipped to “The Orchid Eaters” in the June 2006 issue of Africa Geographic, I quickly realised the magnetism of these plants goes far beyond what the eye can see. Like Orlean’s book, Aisling Irwin’s article portrays orchids as an “obsession” that is “entrancing all layers of society.” This time, however, orchid tubers, not orchid flowers, are the objects of desire. And, far from Laroche and his beloved Fakahatchee Strand, the people with a passion for orchids are the people of Zambia in southern Africa.

Irwin reports that Zambians have recently acquired an insatiable appetite for chikanda – a dish made from pulverized orchid tubers, ground peanuts, salt, red chillies and soda ash. (Another author – who must actually enjoy sandwich meat – calls the dish both a “veggie delight” and “Zambian bologna.”) What seven years ago was the speciality of one Zambian tribe has become a countrywide staple – stirred, stewed and spiced by village women, shared by families, and sold at markets, restaurants and barrooms across the country. The trade in orchid tubers and chikanda is an important source of income for many Zambians.

Zambians are not the first people to eat orchid tubers. According to Irwin, people in 16th-century England used salep (powdered orchid tubers) to make an eponymous tea-like drink. Salep is also the key ingredient in salepi dondurma, or orchid ice cream – a Turkish speciality. The problem, however, is that many orchids are protected species. There are un-surmounted challenges to cultivating orchid tubers for harvest, which means tubers are currently unearthed only in the wild, where they are fast disappearing. In fact, Zambians now turn to neighbouring Tanzania to supply their orchid-tuber fix because tubers have become so difficult to find in their own country.

Unlike orchid flowers, orchid tubers’ potato-like appearance is in no way eye-catching. But, it seems the flowers and tubers share one common font of allure – their fragile, breath-taking elusiveness. Orlean writes that some exceptionally rare orchid plants have sold for more than US$25,000. If the rapid depletion of orchid tubers continues in Zambia and Tanzania, who knows how much a cake of chikanda might one day cost. It goes without saying, however, that the cost to biodiversity will be even greater.

1 comment:

I have read this kind of story sometimes, I mean a similar plot, it's funny when you sometimes found recipes inside of a story.

Nice blog.

Post a Comment